When newer actors get work on films or television shows, there is sometimes a bit of a learning curve when it comes to delivering for the camera, especially doing multiple takes of the same scene.

There are so many factors that come into play beyond our simple viewpoint as actors. We’re usually focused on finding our marks and working with our scene partners on creating a genuine connection – as it should be of course! – that we sometimes can’t see the forest for the trees.

But if you want to take your acting to the next level, it’s important to keep in mind that there is a much, much bigger picture hovering over all of the work you’re doing down in the trenches. That’s a useful metaphor to begin to imagine the larger world you’re a part of: think of yourself the actor as grunt on the front lines. But try to imagine what the generals are seeing, and how you can make their jobs easier when it comes time to edit together a finished product.

If you can learn some tricks to do just that, you’ll be able to vault your on-camera career ahead a few notches in the blink of an eye. Here are a few things to keep in mind if you want to make directors, cinematographers and editors happy, and ensure that your hard work ends up on the screen and not the cutting-room floor!

1. Don’t Change The Objective

There is so much that can change from take to take, differences that an audience might not be able to identify, but which nonetheless mark a particular scene as “The One” and leaves others in the dust. Something that you should never change however is your objective. Make sure you bring the same clear, playable objective to every single take or you’re asking for trouble. Think of it this way: for a given scene in a movie or television show to go longer than two minutes is a rarity. So it’s vital that what you bring to it is consistent, and crystal clear. If you’re still a little fuzzy on what exactly is meant by an objective, there are a couple of must-have books: Michael Shurtleff’s “Audition,” and “The Practical Handbook for the Actor,” written by a group of actors who worked with David Mamet and William Macy in developing a clear, coherent and simple checklist of ways to discover and act your objectives. In the meantime, a useful shorthand is to take Shurtleff’s phrase, “what you’re fighting for” in the scene to substitute for the word “objective.” This is what you want, what you’re doing here in the scene. And of course, any scene revolves around characters trying to get what they want. That part is inherent to the script, the arc of the story, and the arc of the individual character, so it doesn’t change. What can and does change from take to take on camera or from night to night on stage is what tactics you use to try to achieve it. This is where the “action” part of acting comes in – because that’s what we are doing after all: by ACTING we are performing an ACTION. There are numerous lists out there of “actable verbs” but here’s a handy PDF of a few to get you started. So just make sure that the verb you choose supports the objective your character is trying to achieve, but then feel free to plug in different verbs (actions) to play from take to take to keep it fresh.

2. Blocking

But no matter where your various tactics take you, whether you are “bullying,” “begging” or “cajoling” to try to get what you want, you simply can’t change your blocking. Too many younger actors when they get on set make the mistake of thinking freedom to act means freedom to move wherever you want. Remember that the space you see on the set isn’t really the space you get to work with. The actual space may be a huge, cavernous soundstage, but the space you are actually working within is what the camera sees, and what the director wants to show. So if you end up changing up your blocking as a result of going all Pacino in a particular take, it’s likely to wind up in the editor’s recycle bin. What’s more, when you’re working with a camera, crew, and other actors in that very tight, very limited space of the frame of the shot, you just don’t have the freedom to change a whole lot, physically speaking.

3. Eye line

Now we’re getting into the nitty-gritty of thinking outside our actor’s box and looking at a production through the lens of an editor or director. Much the same as with blocking, your eye lines must remain consistent from take to take if it’s going to end up in the final cut. You are likely not the only actor in a scene, and even if you are, there are probably going to be multiple takes of you from various angles that are eventually going to be cut together to form a coherent whole. Any time your eye line shifts from one take to another it creates an inconsistency and renders one take or another unusable if it doesn’t match the others. Work with your director and your scene partner to discover what works best as far as your eye lines go over the course of the scene and stick with it. This doesn’t mean you have to be an automaton; just remember that cutting together several takes from several different camera angles is tricky enough as it is – if your gaze is all over the place from take to take it just won’t work. Another behind-the-camera trick that is useful to keep in mind is that the director and the editor aren’t automatons either, simply taking whatever the actors do and slapping it together to make a coherent time line. They are trained to guide the viewer’s eye to where they want him or her to look. The director and the editor have a pretty good idea of what’s important in the scene, and they are using the actors to tell the audience what that is. You changing your eyeline can blow that up and render a take unusable.

4. Props

This relates to both the above notes and probably isn’t particularly surprising, but nonetheless it is a rule that gets violated a surprising amount of time: props must be used in the same way and in the same place in every single take. Don’t make your editor’s job harder by going all crazy and slinging your jacket over your left shoulder for one take when it’s been the right shoulder all along. The idea of all of this is to make it easy for them to look at using all your takes so they can use your best ones and show you in your best light. Don’t limit their palette. Lock these physical things in and then forget about them, because it’s time for that acting to really begin.

5. Emotion

One thing that’s often surprising is where you might go emotionally just from changing your tactics. And if you are open to receiving these new emotions – perhaps feelings you never even imagined stemming from that particular scene when you were rehearsing it – you can take yourself and your audience to surprising new places. Back to the tactic examples of “bullying,” “begging” or “cajoling.” Have you ever wanted something so bad it almost made you cry tears of frustration? That might occur if you hit “begging” just right. “Cajoling” can easily turn into a kind of seduction, can’t it? You might be surprised where a scene goes if you open up that avenue. And who hasn’t been surprised to see someone unexpectedly using “bullying” tactics at one time or another? All of these can create emotional colors and shades that are different from what you might expect, and different from take to take, but which nonetheless remain consistent with the overall piece and the scene. Take the improv imperative “yes and” to a whole new level with your emotions and see where it leads!

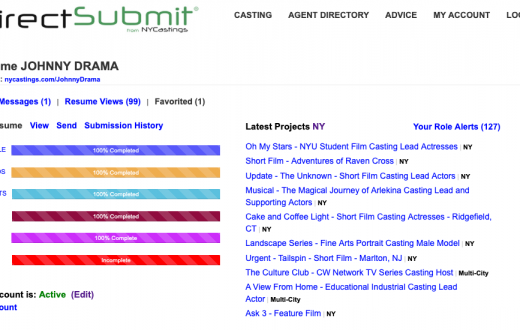

And don’t forget, you have to get yourself in front of the camera first to show them what you’ve learned. Be sure to self-submit to NYCastings and get your face in front of the best in the business!